UNF EXCAVATIONS EXPOSE ACTIVITY AREAS, PITS, HEARTHS, AND BUILDING REMAINS IN THE CENTER OF THE MOCAMA TOWN OF SARABAY

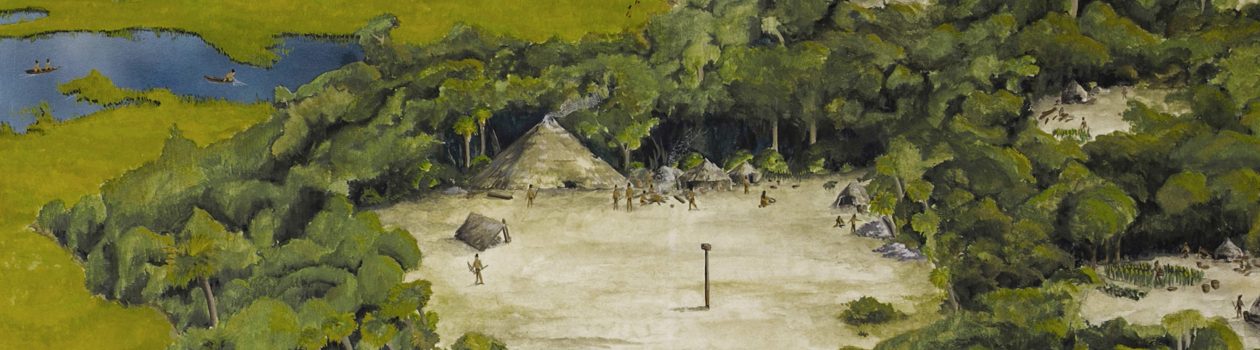

The Timucua-speaking Mocama of northeastern Florida were among the first Indigenous populations of Florida encountered by European explorers in the 1560s. Documents written by the French and Spanish chroniclers vaguely describe Timucua settlements as consisting of circular houses linked to a centralized council house fronting a plaza and ball field, with chiefly residences nearby. A formal layout suggestive of a town rather than a village. While Theodor de Bry depicts a fortified “Timucua village” in his 1591 engravings, many archaeologists reject the notion that Timucua towns were surrounded by a wooden wall.

From an archaeological perspective, we lack any real understanding of what Mocama towns or villages looked like. The absence of broad-scale testing at any Mocama site recently drew us to the Armellino archaeological site, the suspected location of the Mocama town of Sarabay. As part of the Lab’s Mocama Archaeological Project, UNF undertook one of the most intensive and extensive excavations at a Timucua town in the state of Florida, beginning in 2020. Over the past four years, we have opened a broad section of the site in search of activity areas, houses, and other buildings associated with Sarabay. The project has allowed UNF students and volunteers the opportunity to touch the Indigenous past of northeastern Florida.

BRIEF HISTORY OF SARABAY

“I was advised by some of our company, who regularly went hunting in the woods near the villages, that in the village of Saranai [Sarabay], situated two leagues from our fort [Caroline] on the other side of the [St. Johns] river… there were fields of ripened grain in a very abundant crop”

“…the village of Sarravahi [Sarabay]… was about a league and a half from our fort [Caroline] and on an arm of the [St. Johns] river. It had been my custom to send them [colonists] there each day to get clay for brick and mortar for our houses”

These brief passages, penned in 1564 by the René Laudonnière, signal the earliest known written references to the Mocama (Timucua) town of Sarabay. The French commander of the La Caroline colony goes on to identify “King Saranay” (Sarabay) as among other Mocama leaders who visited Jean Ribault and presented “him with presents according to their custom” on his 1565 return to Florida. Three years before, Ribault had briefly reconnoitered the entrance to the St. Johns River and met with Indians on both sides of the river, before heading north to establish the garrison of Charlesfort on present-day Parris Island, South Carolina.

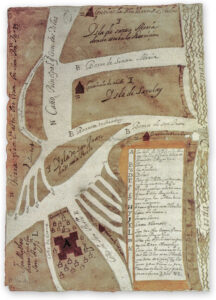

The French La Caroline settlement, established near the mouth of the St. Johns River, lasted only fifteen months, being supplanted by the Spanish in 1565 after a rather bloody eviction. Mentions of Sarabay in the Spanish documents of La Florida are sparse, but we know the community fell under the ministering circuit of Fray Francisco Pareja, who lived nearby on Fort George Island at the Mocama town of Alimacani, known to the Spanish as mission San Juan del Puerto. In a letter to the crown in 1602, Pareja wrote that Sarabay was ¼ a league (less than a mile) from San Juan. This is the last known archival reference to the Mocama town, but the name Sarabay survives on some maps to denote the island known today as Big Talbot.

WHERE IS SARABAY?

Exactly where is Sarabay on the modern landscape of northeastern Florida? As early as the late 1960s, local avocational archaeologist William Jones had suggested Big Talbot Island as the potential location of either Sarabay or Vera Cruz after finding “Indian pottery” and a piece of majolica on the surface of a dirt road. Today, this area is known as the Armellino site, and it lies within Big Talbot Island State Park.

Little was known of the history of southern Big Talbot Island until 1998, when UNF dug more than 550 shovel tests over a three-month period. Those on the Armellino site stood out because many contained Indigenous San Pedro and San Marcos pottery, which we now know the Mocama made during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Nowhere else on the island do we find these Indigenous pottery types in such large numbers, clearly marking the presence of a Mocama settlement that matches documentary and cartographic evidence for the placement of Sarabay.

EARLY UNF ARCHAEOLOGY AT SARABAY (1998-1999)

Following on the heels of our shovel test survey, UNF returned to the Armellino site in 1998 and 1999 to conduct two archaeological field schools. Over the course of two summers, a large block (A-B) covering an 8-x-7-meter area was excavated. An impressive collection of artifacts and features were unearthed. Of note was a section of a wall trench structure. About one-fourth of the building was exposed in the excavation block, with its full size estimated at 6.5 meters in diameter. Along the inside wall of the building, we encountered a nearly complete San Marcos jar with cane punctations along its rim. Inside the vessel was a complete giant Atlantic cockle shell. Subsurface pits of assorted sizes were located inside and outside of the building, some of which contained charred corncobs. Wall trench construction is unique to this area of Florida, suggesting the building may have served a special function or belonged to a high-status family within the community.

Midden contexts and several pit features contained burnt corn cobs and kernels. Radiometric assays on two specimens date the corn to no earlier than 1450. These results, corroborated by radiocarbon dating of corn on other northeastern Florida sites, bolsters our belief that maize was a late addition to a predominately estuary-marsh-oriented Indigenous subsistence economy of northeastern Florida.

In addition to thousands of Native American potsherds, UNF students found modified animal bones, shell artifacts, and a small handful of lithic items. European goods included pieces of olive jar, wrought iron nail fragments, and a brass scabbard tip, likely of Spanish origins. Whether these were acquired via trade, gift exchange, or payment is unknown, but what is clear is that the area we excavated postdates 1562. The scabbard piece and olive jar sherds further imply a post-1587 date, and the San Marcos wares are undoubtedly seventeenth century. So, what we appear to have uncovered is a section of Sarabay occupied between at least 1560 and 1620.

SARABAY PROJECT (2020-2023)

Fast forward 21 years to the fall 2020. Social distancing and wearing masks in the muggy Florida months of August through October are not conducive to block excavations, but that is what must be done when excavating during a pandemic. UNF’s 2020 summer field school was cancelled because of the COVID outbreak but was successfully moved to the fall semester. Field time was limited to 3-days a week with most of the 12 students spending only one or two days a week on site. Despite these restrictions, exhilarated and highly motivated students excavated Block C, an irregular shaped area measuring 18 x 5 meters. It lies less than 20 meters northeast of Block A-B dug in 1998-99. UNF students returned to Sarabay in 2021, 2022, and 2023. To date, we have excavated 132 1-x-2-meter units and 4 1-x-1-meter square (268 square meters). Most were combined to form Block C, which covers 240 square meters.

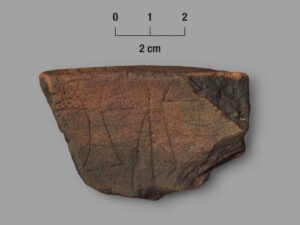

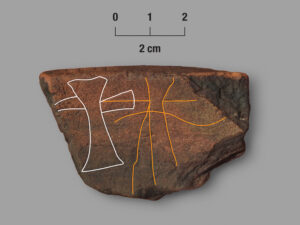

Investigations at Sarabay are ongoing, so we offer only a few brief and general observations. First, we believe our excavations have exposed portions of a core section of the settlement. More than 11,000 Indigenous potsherds have been analyzed to date. San Pedro pottery dominates the assemblage followed by San Marcos. The context of recovery, combined with statistically identical radiometric dates on sooted San Pedro and San Marcos sherds, suggests an in-situ transition in the production of San Pedro into San Marcos around 1600 at Sarabay. European artifacts include more than one-hundred Spanish olive jar sherds, 15 colorful majolica plate fragments, and several pieces of Mexican Red Painted earthenware along with several hand-wrought iron nails and a brass scabbard tip. Two Indigenous made artifacts decorated with Christian imagery: a potsherd with a cross incised on its interior surface and a local ribbed bivalve shell shaped into a cross with a dot and radiating lines thought to represent a monstrance pin or symbol. In addition, a brass or bronze religious medal was uncovered in 2023. At present, the combined assemblage is thought to date to ca. 1580-1630.

In terms of architecture, UNF excavations over the past four years have unearthed the remains of a second Native structure, located about 25 meters northeast of the one discovered in 1998. A little less than half of this post-in-the-ground building has been exposed, but it is suspected to measure about seventy feet in diameter. Its size and shape are suggestive of a council house or other public building. Additional postholes and pits have been identified inside and outside the structure, including an interior pit measuring about three feet in diameter and three feet deep. A unique, roughly circular trench, measuring a little more than 2 meters in diameter and containing 4 posts, was discovered in 2023.

Each year of excavations at the Armellino site has strengthen our belief that it is the on-the-ground location of the Mocama town of Sarabay. Our very preliminary interpretation of excavation results at this time proposes the presence of an elite or special-use structure, a large building, and nearby refuse middens within a 180-x-120-ft area.

Through the years, our research has benefitted from the unwavering support of Big Talbot Island State Park, Friends of Talbot Islands State Parks, North Florida Land Trust, and Timucuan Parks Foundation.

UNF STUDENTS EXCAVATING AT SARABAY

The UNF Summer A Archaeological Field School is a 6-week field practicum that offers an extraordinary opportunity to gain hands-on experience in archaeological fieldwork. The course focuses on the Armellino site (8DU631) at the south end of Big Talbot Island, within Big Talbot Island State Park — the archaeological location of the Mocama town of Sarabay. A maritime forest, with dense vegetation in areas, covers most of the site.